Written By Colin Parker Griffiths

Edited By Aiya Hyslop-Healy

Introduction

Examining Edgar Degas’s depictions of female subjects in his artworks provides a pragmatic way of analyzing the patriarchal gender relations and ideologies of nineteenth-century Paris. The works Dancers In Repose (1868), Resting (1876-1877), and The Tub (1886) demonstrate Degas’ underlying misogyny and illuminate the social conditions of the time period characterized by men’s internal anxieties regarding the increase of working women in society, and more specifically, the presence of female sex workers. Degas employs an overbearing voyeurist perspective in the three artworks, creating a phallic masculine intrusion within women’s private moments that mediates his desire and revulsion for women. By fixating on female sex workers as subjects for his artwork, and drawing with an eye restricted to the objectifying male gaze, Degas contributed to the misogynistic discourse of nineteenth-century Paris that was preoccupied with shaming female sex workers and repressing women’s agency.

The Ballet

The work Dancers in Repose (1868) (see fig. 1) depicts two female ballet dancers in a visibly exhaustive state while waiting on a bench in a dance studio. By virtue of Degas’ artistic choices, the viewer of the artwork is positioned as a predator hunting its oblivious prey; the dancers tiredly stretch their bodies unbeknownst to their inconspicuous male spectator. During his lifetime, Degas was rather vocal about his perspectives of women, making it publicly known that he saw women as akin to pure sensual animals, and often describing ballet dancers as ‘little monkeys” (Skelly). For an artwork depicting ballet dancers, the position in which Degas places the two women is rather unusual. Instead of visualizing the elegance and dynamism of their ballet technique, he depicts them in repose, lazily hunched forward with a pronounced bend in both the arms and knees as they grip their legs and feet—much like the posture of a little monkey. Metaphorically, Degas draws the curtain for the male spectator of their graceful, feminine performance that is seen on the stage. The voyeuristic nature of the artwork now removes the spectator from the perspective of an audience member, and places them into the private moments of these dancers. In doing this, Degas appeals to a patriarchal society that is both fascinated and repulsed by the female body (Callen 105).

Due to his bourgeois status and acute interest in ballet, Degas belonged to the les abonnés—a group of wealthy and powerful men who greatly funded the Paris Opéra. Being a ‘backstage gentleman’ came with its perks; when renting a box in the venue, it was commonplace for a ballerina to be given in exchange. In the ballet world, many of the young female dancers of the Paris Opéra were described by the bourgeois as petits rats—young women whose impoverished parents enrolled them in ballet in hopes they would someday achieve prima ballerina status and thus provide for their families (Schacherl 32-27). However, achieving prima ballerina status was unlikely due to the competitive nature of the industry, and because the checklist for becoming a prima ballerina demanded that she not only have perfect technique, but also the perfect body and beauty (which for the most part, remains true in the ballet industry today). Even if she met all the criteria, the immense physical strain of ballet on the body is causal to a very early retirement. Additionally, after the end of the Romantic era in the late 1860s, the Paris Opéra was in a period of economic decline, meaning that the déclassés who failed to become prima ballerinas were forced to find income elsewhere (Schacherl 12-13). Because of the institutional organization of the Opéra, les abonnés always happened to be closeby with opportunities for the women to create a profit if they were willing to transgress the social values of the time. One female dancer who left the ballet made the statement: “As soon as she enters the Opéra her destiny as a whore is sealed. There she will be a high-class whore” (Lipton 74).

Most bourgeois men saw the Paris Opéra Ballet as an exhibition, not of dance performance, but of young women’s bodies, the youngest and prettiest available for purchase. For Degas and his male comrades, what made the women ugly despite them being the ‘crème de la crème’ of female sex workers, was their impoverished status and transgression of supposedly respectable morals. More importantly, working women in general, whether receiving income from the ballet, sex work, or any other profession, threatened the dissolution of male ownership over women during this moment in history wherein women were beginning to have increased social and economic mobility (Lipton 102). Degas frames dancing female subjects as sexually transgressive creatures instead of highly trained dancers in his effort to avoid confronting the existing culture of misogyny that values women’s bodies as a purchasable commodity.

The Brothel

Degas’ involvement with sex workers is further demonstrated in his monotype Resting (1876-77) (see fig. 2), which also illuminates the connection between the ballet world and the brothel in nineteenth-century Paris. Throughout his career, Degas created 33 monotypes depicting the brothel with characters from the novel series Monsieur et Madame Cardinal (1872) and Les Petites Cardinal (1880) written by his close friend Ludovic Halévy, a well-known nineteenth-century writer. The novels follow the story of a stage mother who sells her two dancing daughters and builds for them a network of male clientele through the Paris Opéra. In the story, one of the Cardinal daughters becomes a ‘high-class whore,’ while the other marries into aristocracy (Schacherl 37-38). Degas based some other monotypes on Edmond de Goncourt’s novel La Fille Elisa (1877), another friend of his who was an author and wrote about an impoverished young woman becoming the star of a brothel in Paris, but eventually meeting her demise. Evidently, Degas took an ambiguous interest in these stories, as he illustrated these characters in various monotypes and inscribed ‘La Fille Elisa’ in his personal notebook several times (Kendall et al. 44). Given the fact that more than one of Degas’ close male friends during this time period wrote a novel about the fate of female sex workers, I believe it is a well-founded claim to make that this is representative of how Degas and his circle of bourgeois male friends viewed women and thought about female sexuality at the time.

Although it is unknown if Degas created Resting (1876-77) out of inspiration from one of these novels, this artwork nevertheless contributed to—and was a product of—a larger misogynistic discourse around female sex work that was taking place within the upper-class Parisian society of the nineteenth century. Male artists’ and authors’ literary and pictorial representations of female sex workers and the brothel worked to sustain an erotic interest for male viewers; the male client, or the male ‘consumer’ of women’s bodies, was a figure that most men could self-identify with. In this monotype, Degas positions the spectator as a male client sitting across from two female sex workers in the salon. One woman sleeps naked, laying horizontally on the furniture, while the other sits upright with her hand over her pubis, looking distraught and returning her gaze to her perceiver. Placing the spectator in this perspective of the male client—already inside the salon—decreases men’s anxiety around the imminent discovery of the brothel. By doing this, Degas introduces men to the space and imposes them as a client through the arbitrary male gaze, providing them with comfort to enter the brothel if they haven’t already.

The root of this anxiety men had around female sex workers in nineteenth-century Paris lies in the fact that their desire for sex workers and endeavors within the sex trade were at risk of public discretion. Degas’ decision to frequently employ voyeurism in his artworks—never positioning the male subject inside the frame, but instead showing us his perspective—derives from men’s collective fear of becoming the subject of scandal, disempowered under the gaze. He configures this work with a one-sided erotic tension between the male spectator and the female sex worker, a tension that provides the man with an ambivalent thrill by dancing on the dangerous edge between his public persona and private endeavors (Callen 101-104). By removing the male client from view, Degas protects his privacy; the only gaze able to perceive him belongs to the woman who sits across from him, which he has already rendered meaningless inside the walls of the brothel (Callen 101).

The Bath

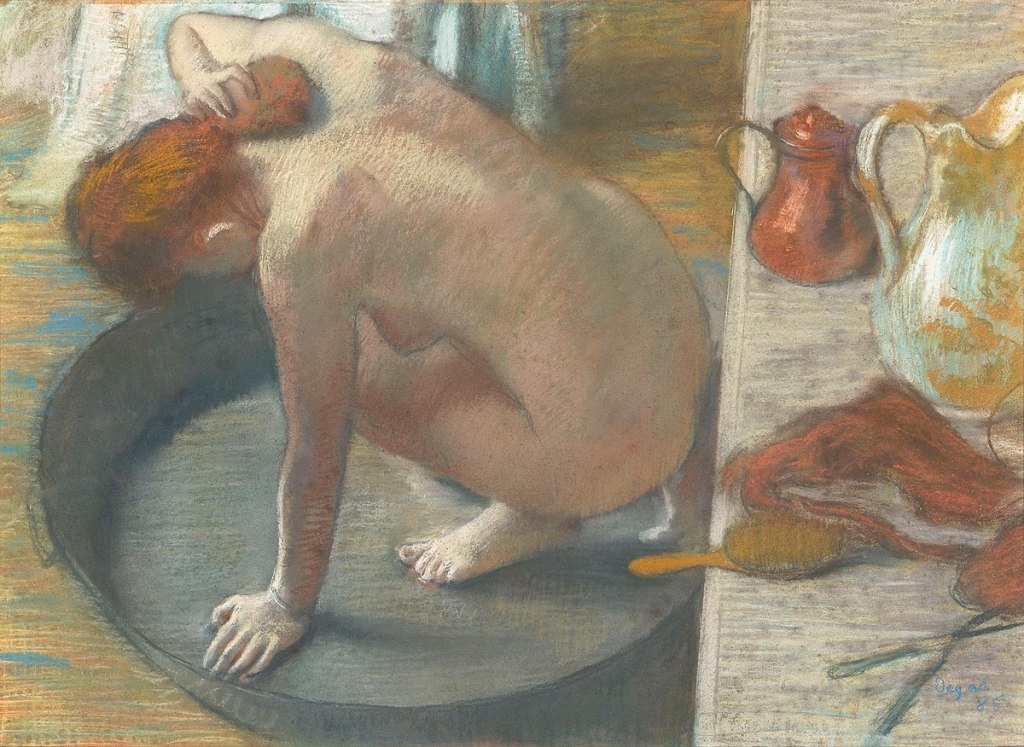

The Tub (1886) (see fig. 3) is one of several artworks by Degas that depict women bathing through this same voyeuristic perspective. With this change in subject matter, he extends his misogynistic anxiety around female sexuality into the social discourse of hygiene that circulated in nineteenth-century Paris. The position of this woman’s body is strikingly similar to that of the women in Dancers in Repose (1868)—she is awkwardly crouching inside a metal basin with her back hunched over, and one arm angled up behind her head while she scrubs the back of her neck with a sponge. With reference to the common formal conventions employed by male artists during the nineteenth century, it becomes clear that Degas is positioning this woman as a sex worker, offering the consumption of her body to the male viewer through this keyhole perspective. Depicting a woman with red hair was often a way for male artists at the time to signify that the woman was a sex worker or a lesbian, as this reflected the existing cultural beliefs about women with red hair (Skelly). On top of the dresser lies the full, intact length of the woman’s hair that she has just cut from her head, a formal choice made by Degas to further emphasize the narrative of a woman selling her body. Additionally, the spots of discoloration on the skin of her backside can also be associated with visual signs of illness (Skelly).

With regards to conventions of hygiene during the 1860s in Paris, a woman who bathed excessively ought to be a sex worker (Skelly). This internalized ideology around women bathing is also seen in Édouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1863), as one of the female sex workers is seen washing herself in the pond. At the time, for a woman to immerse her entire body in water was considered equivalent to sexual deviance. Thus, ‘morally hygienic’ women did not bathe regularly (Skelly). Water was also seen to have connotations of female sexuality within Catholicism; Catholic women who bathed on occasion were expected to wear robes and close their eyes while doing so to avoid consuming their own naked bodies through gaze and touch, and to restrict the water from freely engulfing her body. Typical hygiene practices for the bourgeois in this period consisted mostly of wearing clean linen that gently exfoliated old skin and absorbed perspiration odors (Callen 144-145).

In his effort to repress and shame female sexuality by intentionally using stigmatizing visual tropes in his pictorial representations of sex workers, Degas seeks to suppress the agency of these women, and mediate his own desire to sexually engage with them by offering their moments of privacy to an audience. Whether he had models pose for these scenes, or they were created out of his imagination, they collectively work to reflect not only his own misogynistic anxieties, but that of the broader bourgeois society of nineteenth-century Paris.

Conclusion

Certain art historians employ the method of social art history to attend to a broad range of relevant social relations between artists, artworks, institutions, and ideologies that construct the social order of a certain culture and time period. In doing this, they reveal how artworks are always influenced by the cultural context of the time in which they were created. Investigating the works of Degas using this method reveals the specific ideologies around women’s sexual agency, and respectable forms of femininity within nineteenth-century Paris. Specifically, his works Dancers In Repose (1868), Resting (1876-1877), and The Tub (1886) demonstrate his personal misogynistic anxieties around female sexuality that were reflexive of the broader patriarchal beliefs and discourse taking place during the time period.

Bibliography

Callen, Anthea. The Spectacular Body: Science, Method, and Meaning in the Work of Degas. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995.

Kendall, Richard, et al. Degas: Images of Women. Liverpool: The Tate Gallery, 1989..

Schacherl, Lillian. Edgar Degas : Dancers and Nudes. Translated by John Ormrod. Munich & New York, Prestel Publishing, 1997.

Lipton, Eunice. Looking into Degas : Uneasy Images of Women and Modern Life. Berkeley, University Of California Press, 1986.

Skelly, Julia. “Feminist Art Historians Critiquing Male Artists.” Feminism in Art and Art History, Undergraduate Course Lecture. 3 October 2022. McGill University, Montréal.